The role of dairy farming as a driver of the badger cull

In March, the government announced plans to overturn its promise to phase out the badger cull. Instead, they plan to reduce the badger population even further, continuing to scapegoat this majestic species whilst ignoring the real driver of bovine tuberculosis: dairy farming.

Some people believe that culling badgers is the solution to the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB) in farmed cattle. While cows can catch bTB from other animals, including wildlife, they are also more likely to catch the disease if kept in poor conditions or suffering ill health. This is because respiratory diseases, like bTB, spread more easily when animals are housed in crowded, poorly ventilated sheds or confined closely together in transport vehicles or at market [1]. Unfortunately, this is exactly what modern dairy farming looks like.

Dairy cows are farmed to exhaustion, which takes a huge toll on their bodies and their ability to withstand infectious diseases and illness. For example, in unfettered conditions, a female cow will produce around 1,000 litres of milk per lactation and carry only 2 litres in her udders at any one time. But in modern dairies, she’ll be expected to produce between 6,000 – 12,000 litres per lactation and carry around 20 litres in her udders. Combine this with being housed for 6 months of the year (or longer in ‘zero grazing’ systems) in close proximity to hundreds of similarly unhealthy cows and it’s not surprising that 94% of bTB cases are transmitted from cow to cow – not from badger to cow.

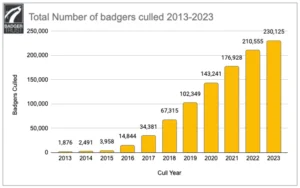

Despite this, badgers continue to be persecuted. In England in 2023, at least 19,570 badgers were culled under government-issues licenses and 20,243 cows were slaughtered. According to the Badger Trust, in some areas of England, the government can’t find any more badgers to kill with ‘minimum kill targets’ being repeatedly missed because badger populations simply aren’t recovering. Disturbingly, an independent report found badgers taking over 5 minutes to die from bullet wounds, blood loss and organ failure raising serious animal welfare concerns. In addition, badgers are not tested for TB before being killed (the government has repeatedly rejected calls for testing and vaccinating badgers) meaning thousands of healthy animals are being needlessly murdered every single year.

Table produced by the Badger Trust based on data for the 2023 cull period.

The bigger picture

Animal farming creates conditions that are ideal for the rapid emergence and spread of disease. Huge numbers of highly stressed animals bred for fast growth and high production, who are housed in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions provide the perfect breeding ground for infections. And it’s not just bovine tuberculosis (bTB): outbreaks of avian flu are more likely in countries, including the UK, who operate large-scale, intensive chicken farming [2,3], while cases of swine flu have increased in line with the intensification of pig farming seen over the past 50 years.

As long as the relationship between humans and animals is one based on production and profit rather than respect and compassion, animals will continue to suffer – from the cows exploited as milk machines to the scapegoat mass killing of wildlife.

Help change this relationship for the better by adopting a cruelty-free, vegan lifestyle today. Find out more here or grab your FREE guide.

References

[1] Schuck-Paim, C., Alonso, W.J., & Slywitch, E. (2023). Animal welfare and human health. In A, Knight, C. Phillips, & P. Sparks (Eds.), Routledge handbook of animal welfare (pp.321-335). Routledge.

[2] Shortridge, K.F., Peiris, J.S.M., & Guan, Y. (2003). The next influenza pandemic: Lessons from Hong Kong. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 94(1), 70-79.

[3] Greger, M. (2006). Bird flu. New York: Lantern Books.