The suffering of farmed pigs

Most pigs in Britain are raised in crowded, dank sheds and get to taste fresh air only briefly while being shunted to and from the breeding units.

Contrary to popular belief, pigs like to keep themselves clean and are not happy wallowing in excrement. Yet the majority of farmed pigs are often forced to live standing and lying in their own waste. Research shows that in natural conditions pigs are highly active, spending 75 per cent of their day rooting, foraging and exploring. Condemned to a life of misery and squalor, such activities are impossible for factory farmed pigs.

The life of the typical breeding female is particularly harsh and relentless. The majority are housed permanently indoors. Sows are repeatedly made pregnant and their babies taken away from them. They are first impregnated when six to eight months old – increasingly via artificial insemination. As a result of selective breeding, sows now typically give birth to 10 or even more piglets, compared with four or five in the wild.

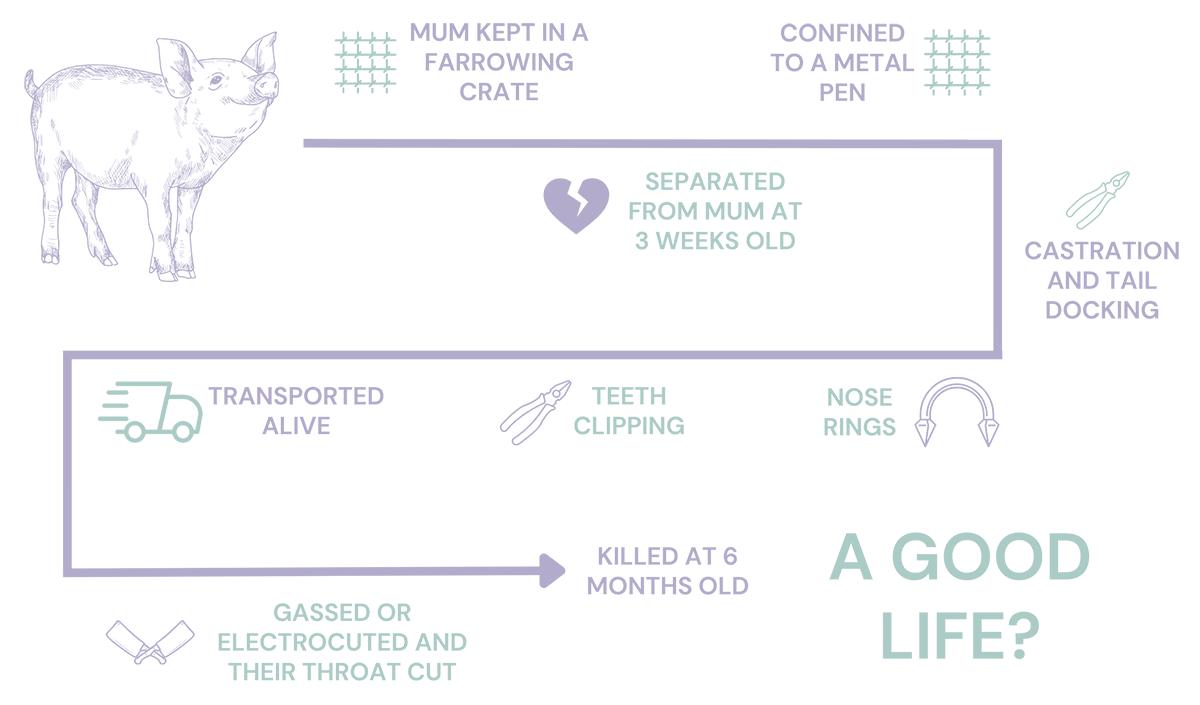

The sows are put into ‘farrowing crates’ – one of the most barbaric tools of the factory farming industry – about a week before they give birth and are kept there for about a month afterwards. Farrowing crates are barren, metal and concrete cages, just a few inches longer and wider than the sow herself. She cannot step forwards or backwards or even turn around for the duration of her restraint. Her newborn piglets are forced to suckle from a small area known as a “creep”, adjacent to, but separate from, their mother. The justification for the use of the farrowing crate is that the sow would otherwise crush her young. Research, however, shows that, ‘given the right management’, piglets delivered in loose housing units suffer no more deaths than are found in farrowing crates.

Although the natural weaning process takes two to three months, piglets are usually taken away at three to four weeks so that their mothers can be impregnated again. The separation – which causes stress to both mother and offspring – increases the speed with which the sow comes into season and thus she becomes capable of having another litter sooner than nature intends.

Mutilated and fattened

The piglets are moved from the farrowing unit into concrete pens, or metal cages with perforated concrete or slatted metal floors. These newly-weaned animals, desperate for their mother’s teats, often frantically try to suckle their young penmates or bite their tails. The industry’s “remedy” is to amputate the lower part of the tail – a painful mutilation that can also result in infections in the dirty farm environment. Most piglets also have their pointed side-teeth clipped down to the gum in the first few days of life. This is said to prevent them from lacerating either the sow’s udder or the faces of their litter mates. Once again the industry ignores the real problem – namely, the piglets are being forced to compete for teats in a barren, unyielding metal and stone environment with an unnaturally large number of litter mates. It is against welfare regulations to ‘routinely’ amputate the tails or clip the teeth of pigs, but this rule is flouted on many farms.

After about six weeks, the young pigs are moved to similarly unsuitable rearing pens, or new farms, for final fattening on a high protein diet. Bred to grow much faster than nature intended, piglets are often unable to support their own weight – leg deformities are common. Heart and respiratory problems are also endemic. A lifetime spent on hard concrete floors causes breeding sows to suffer a high incidence of lameness.

Infections run rife on pig farms due to the filth, the heat and the overcrowded conditions. Their feed is often laced with antibiotics, simply to keep them alive.

From farrowing unit to sausage meat

The mother, meanwhile, following the removal of her piglets, is returned to a small group pen with other weaned sows – ready to be re-impregnated within a matter of days. The strain placed upon these breeding sows is visible in the many health problems they suffer. These include brittle bones and leg deformities, resulting in lameness, which in turn leads to an inability to ‘posture’ properly for mating. This is an important reason for the trend towards artificial insemination. After three or four years of relentless exploitation, breeding females – as well as stud boars – are ‘spent’ and sent to slaughter. They will usually be turned into cheap meat products such as pies and sausage meat.

Transported and slaughtered

After four to seven months, pigs not selected for breeding purposes are sent for slaughter. Some die during transit due to stress caused by overcrowding, long journeys, rough handling and extremes of temperature. In Europe, current legislation allows animals to be transported for several days. Pigs can travel for up to 24 hours, provided there is continuous access to water and then they must be unloaded, fed, watered and rested for at least 24 hours before they can travel for a further 24 hours. This sequence can be repeated.

More than 10 million pigs are killed in British slaughterhouses every year.

Hover or tap to view

At the slaughterhouse, pigs are first given a powerful electric shock to their heads – an attempt to render them ‘insensible to pain’ – before their throats are stabbed with a knife (known as ‘sticking’). Electric stunning is reversible so it is vitally important that the stun is delivered for the correct duration, in the correct place and using the correct current; and that the animal’s throat is cut as soon after stunning as is possible (recommended time between stunning and sticking is no longer than 15 seconds). Secret filming by Animal Aid inside 11 randomly chosen British slaughterhouses revealed breaches of this law in almost every slaughterhouse that used electric stunning. If electric tongs are applied incorrectlly they can cause agonising pain and still leave the animal fully aware. Animals who are left too long after stunning can regain consciousness before being killed. Even when stunning is done ‘correctly’, some observers believe that animals are simply ‘frozen’, rather than rendered insensible to pain.

Read more about Animal Aid’s slaughter investigation and watch a compilation of footage from our slaughterhouse investigations

Free-range and Organic

It is common for ‘free-range’ piglets to be born indoors because their mothers are kept housed to maximise their breeding potential. The sows give birth in farrowing crates and the piglets are reared outside.

‘Outdoor bred’ pigs are born outside, where their mothers stay throughout their breeding lives. The sows give birth in huts or pig arcs, which are usually lined with straw and also provide shelter. The piglets benefit from the free-range conditions until they are weaned – at three or four weeks old – and then they are moved to indoor systems where the welfare standards can vary considerably.

‘Outdoor reared’ describes a system in which the piglets are born outside and have full access to the outdoors for up to 10 weeks of age before being moved to indoor rearing/finishing units. Ten weeks is still far short of the 17 weeks that pigs suckle and nurse their young in semi-natural conditions.

Under basic organic standards, most piglets stay with their mother and siblings outside until they are sent to slaughter. However, the final fattening phase of organic pigs may take place indoors, provided that this indoor period does not exceed one fifth of their lifetime.

In the UK, more than 90 per cent of all piglets are ‘finished’ in indoor fattening units.

Outside shelter is provided in the form of pig arcs, but this may be inadequate during extreme weather, as modern intensive breeds cannot cope with varying conditions – whether too much rain, snow or sun. They suffer a high incidence of heat stress, respiratory and other diseases, as well as lameness due to the often boggy ground.

Read about our investigations into pig farmingGo Vegan

Killing an animal for food can never be regarded as humane. Animals’ lives are as important to them as ours are to us and none go to the knife willingly. Choosing organic or free-range over factory farmed meat, milk or eggs, continues to cause pain and suffering. The only viable solution to end animal suffering is to adopt an animal-free diet.

Order a FREE Go Vegan guide